So, when are we leaving for Cameroon? This is the top question we get right now; the short answer is “spring and summer 2019, God willing”.

First, recall that we’ve accepted an assignment with the Linguistics Services Team (LST), based in Yaoundé, Cameroon, but serving the Central African Basin in Francophone Africa. We will continue to use participatory research methods to develop writing systems in language communities that need them, so Bible translations will be read with fluency and power. #FluentReadingMakesPowerfulBibles

So when will we begin that assignment? While there is lots to do to make that happen, there are two main issues we are working on right now. The question of James’ schooling I address in another blog entry; the other is our financial readiness. Recall that Wycliffe has a policy that we must be receiving 100% monthly financial support to start a new assignment (which is a good thing). Since we are currently at 74%, that represents a non-trivial difference.

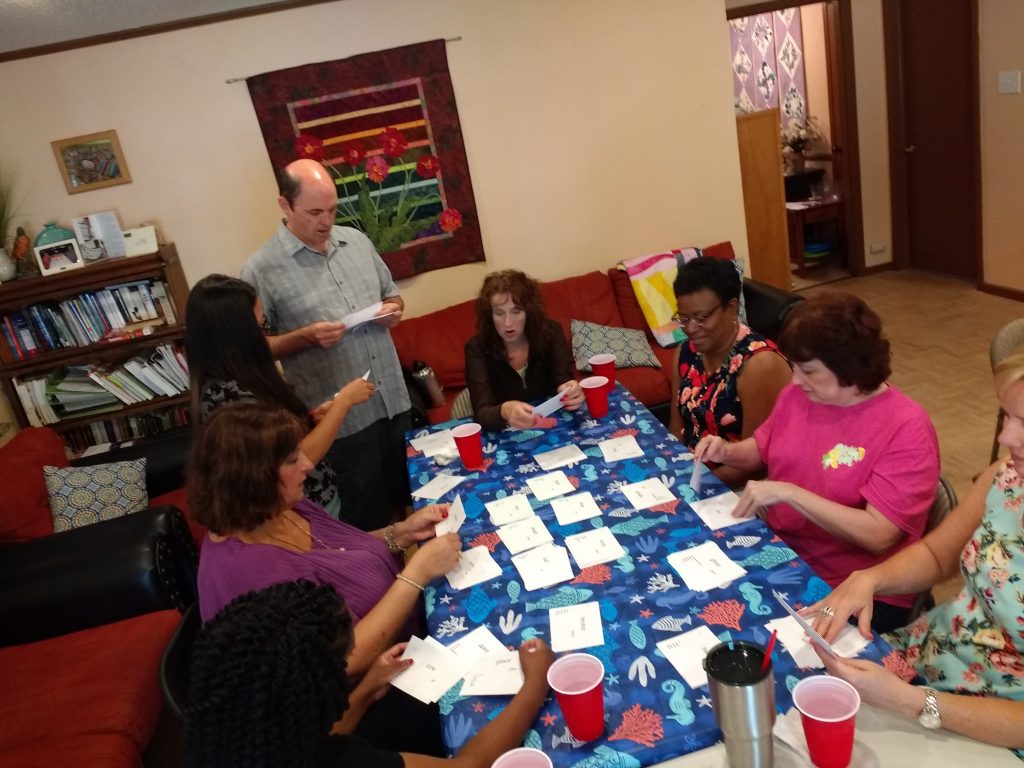

In the mean time, we have plenty of work to do. We are praying and talking to people about our work, individually and in small and large group meetings. But each one must give as he has decided in his heart, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver (2Cor 9:7 ESV). We are also making plans and preparations for the move to Cameroon, trusting that God will provide us the right ministry partners at the right time. If you’d like to hear more about our work, either individually or in a small or larger group, please just let us know. If you have decided to join our Wycliffe ministry in financial partnership, you can do so here.

We currently hope to visit Cameroon in March. There is a linguistics conference one week, and a branch conference the next. In addition to these conferences, a March visit would help us plan and prepare for a move as a family, hopefully in June or July (between the end of school here, and the start of school there). Our kids could meet some of their classmates for the following year, which could really help them transition. And we could see housing and transportation options first hand, as well as the kinds of things that are locally available (and thus unnecessary to ship).

A March trip is something of a bold plan, though. Logistically, in order to buy affordable airfare, we need to buy them in advance. This means we would need to have enough support to justify the trip by about Christmas, or perhaps January at the latest. But such a trip would be worth it; a family move (over the summer) would go much better, as each of us would have more realistic expectations of where we will be moving to.

Whatever comes of this March trip, I (Kent) should be ready to start on my LST work as we have our full budget coming in and get released to our assignment. Some of that work can be done at a distance (I attended a meeting virtually last week!), in addition to the work of selling/storing/packing up our house and preparing for the move.

As we plan this next transition, it feels like we have more questions than answers. How will the presidential election in Cameroon affect stability for this next year? What should we do with the stuff we left in DRC (is any of it worth trying to transport across Africa?) What will we need to make the move to Cameroon (e.g., a vehicle, household setup), and what will that cost? We hope most of these will be settled by the end of a trip to Cameroon in March.

Please join us in prayer that God would provide monthly financial partners for our Wycliffe ministry, such that we would have 100% of our monthly budget by Christmas, so we can make plans for March and June, and get back to serving the Bibleless peoples of central Africa, one alphabet at a time.