I just got back from a workshop where we tested out AZT in a longer workshop, and things went well. I say “longer”, because it was supposed to be three weeks, but we had to isolate after the first day, because of a COVID-19 exposure (the first in our whole community in months). But we got tested:

And then again:

Anyway, it was good to get back to the workshop:

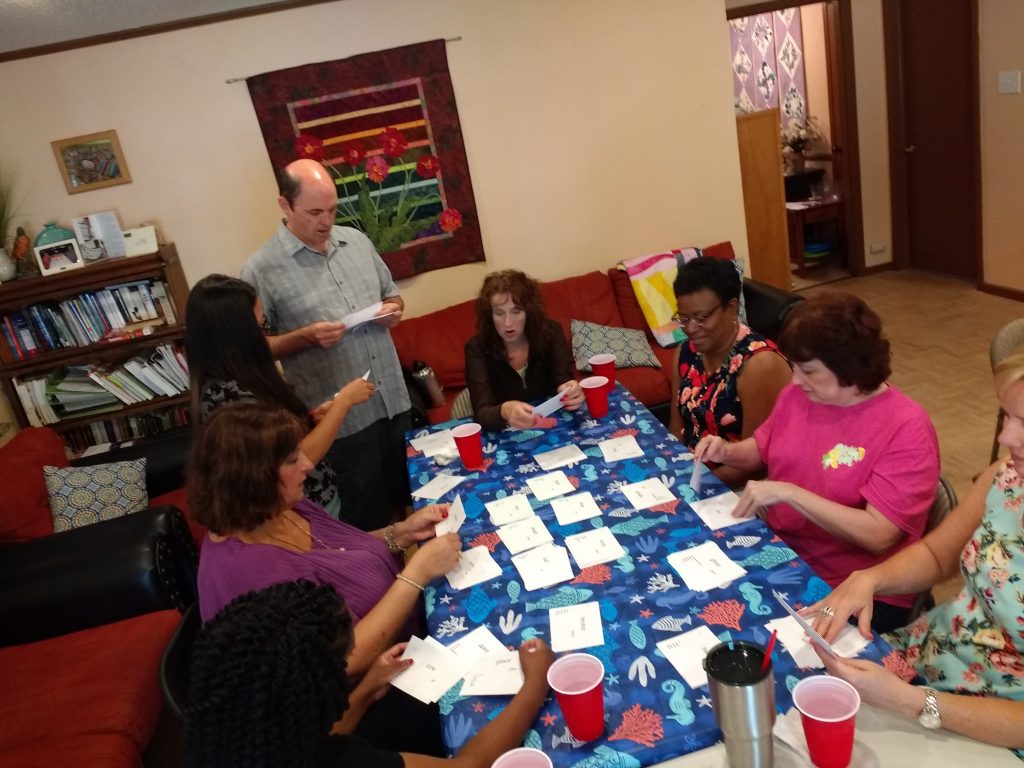

When we debriefed the workshop, I had two main questions for the guys. First, was the tool easy enough to use? One guy responded that he didn’t really know how to use computers, but this tool was easy to use. So that was great news. I had suspected this, and worked for it, but it was good to hear we’re hitting that target.

The other question was about engagement and involvement: did the guys feel like they were actively taking a real part in the work? Again, they answered yes. In the picture above, the guys are talking through a decision, before telling the computer “This word is like that other one”, or “this word is different from each word on this list”. Framing this question is important, because this is a question that people can discuss and come up with a real, meaningful answer, without knowing much about linguistics. If we were to ask them to tell us if this phrase had a floating tone in it (yup, those are real), we would be asking them to guess and make up an answer, since they would have no idea what the question meant —probably just like most people reading this post. :-) But floating tones are important, and we need to analyze them correctly; we just want to get at them in a way that enables the fullest participation of the people who speak the language.

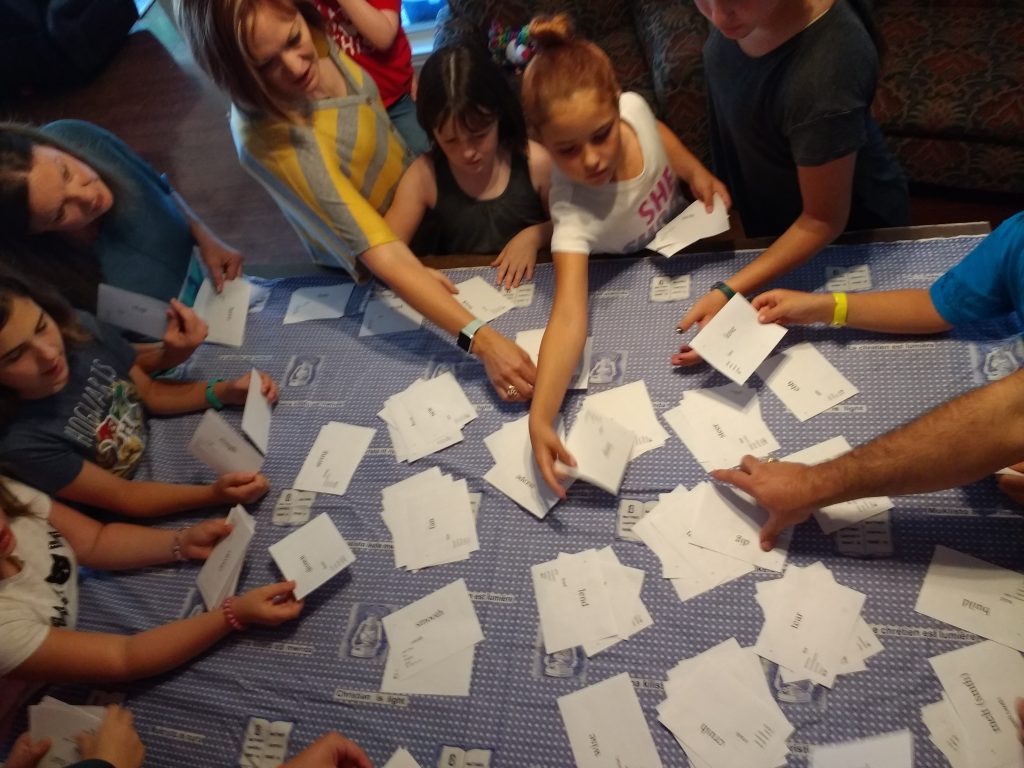

I didn’t come up with this on my own; far from it, I’m standing on the shoulders of giants, who pioneered how to engage people meaningfully in the analysis of their own language. What’s new here is that these methods are modeled within a computer program, so the user is clicking buttons instead of moving pieces of paper around on a table. Buttons are not in themselves better than paper, but when we work on the computer, each decision is recorded immediately, and each change is immediately reflected in the next task —unlike pen and paper methods, where you work with a piece of paper with (often multiple) crossed out notes, which then need to be added to a database later.

The other major advantage of this tool is the facilitation of recordings. Typically, organizing recordings can be even more work than typing data from cards into a database, and it can easily be procrastinated, leaving the researcher with a partially processed body of recordings. But this tool takes each sorted word (e.g., ‘corn’ and ‘mango’), in each frame (e.g., ‘I sell __’ and ‘the __is ripe’) it is sorted, and offers the user a button to record that phrase. Once done, the recording is immediately given a name with the word form and meaning, etc (so we can find it easily in the file system), and a link is added to the database, so the correct dictionary entry can show where to find it. Having the computer do this on the spot is a clear advantage over a researcher spending hours over weeks and months processing this data.

Once the above is done (the same day you sorted, remember? not months later), you can also produce an XML>PDF report (standing again on the giant shoulders of XLingPaper) with organized examples ready to copy and paste into a report or paper, with clickable links pointing to the sound files.

Anyway, I don’t know if the above communicates my excitement, but thinking through all these things and saying “This is the right thing to do” came before “Huh, I think I could actually make some of this happen” and this last week, we actually saw this happen —people who speak their language, but don’t know much about linguistics meaningfully engaged in the analysis of their language, in a process that results in a database of those decisions, including organized recordings for linguists to pick apart later —and cool reports!