You have probably heard someone quote 1 John 1:9, perhaps in its immediate context:

8If we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us. 9If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness. 10If we say we have not sinned, we make him a liar, and his word is not in us.

(1 John 1:8-10 ESV)

I’ve often thought of this as a “Jesus forgives” sandwich on “we sin” bread. That is, I saw verses 8 and 10 as saying basically the same thing, with the sole purpose of supporting v9. But I looked at it more closely recently, and I think John is saying something important here, that we don’t want to miss.

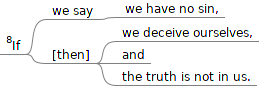

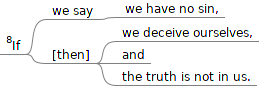

I think this point has to do with two basic human desires: to be right, and to be in relationship. Looking at verse 8, we might see the following structure: That is, we have a basic if/then structure (with an implied then). The if clause contains something we may say about ourselves: we have no sin. This is maybe not something we would say straight out like that, but I think a decent summary would be “I’m right”. Have you never said this? I have. “My condition/position does not contain flaws.” This is a statement about who I am, which is very important in these days of identity wars.

That is, we have a basic if/then structure (with an implied then). The if clause contains something we may say about ourselves: we have no sin. This is maybe not something we would say straight out like that, but I think a decent summary would be “I’m right”. Have you never said this? I have. “My condition/position does not contain flaws.” This is a statement about who I am, which is very important in these days of identity wars.

So what is the consequence of saying “I’m right”? In this verse they are twofold. First, we deceive ourselves. This is, I think, the most fundamental flaw with a worldview that states “I decide/declare who I am”; there is no way to handle self-deception (which is visible in the most basic understanding of human psychology).

The second consequence of saying “I’m right” is that the truth is not in us. Or, you could say we are wrong. In this way, a direct consequence of insisting I’m right is proving that I’m wrong. My insisting that my personal status is “correct” or “OK” makes my personal status “incorrect” and “Not OK”. So much for my desire to be right.

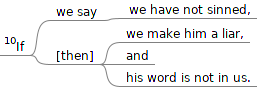

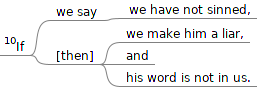

Verse 10, on the other hand, deals with actions and relationship: Again we have an if/then structure, and again the if clause has to do with something we say about ourselves. But this time the statement is not we have no sin, but we have not sinned (or perhaps “I have not done wrong”). While the difference may seem trivial, I think it interesting that the if clause in v10 is talking about what we say about our actions, whereas the if clause in v8 was talking about who we are, or our status. Yes, there is a sense in which if we do right/wrong, we are right/wrong, and vice versa, but they are not exactly the same thing.

Again we have an if/then structure, and again the if clause has to do with something we say about ourselves. But this time the statement is not we have no sin, but we have not sinned (or perhaps “I have not done wrong”). While the difference may seem trivial, I think it interesting that the if clause in v10 is talking about what we say about our actions, whereas the if clause in v8 was talking about who we are, or our status. Yes, there is a sense in which if we do right/wrong, we are right/wrong, and vice versa, but they are not exactly the same thing.

So what are the consequences of saying ”I have not done wrong”? Again, they are twofold. First, we make him [out to be] a liar. (The words in brackets are present in other translations, and are correctly implied even in the ESV, I believe; the verse cannot mean we succeed in changing God’s status to “liar”.) Given that this verse is talking about our actions, what are the implications of this action? I cannot think of many people who would bear being called a liar when they are telling the truth. Claiming that you tell the truth, and that God lies, must have repercussions on your relationship with him.

The second consequence of saying “I have not done wrong” is that [God’s] word is not in us. That is, not only am I personally insulting my creator, but I’m also showing that I don’t speak for him when I speak —since his word contradicts mine. I think this point is aimed at people who want to be seen as doing right on their own terms, but also to identify with, speak for, or somehow represent God. But John says you cannot insult God and claim to speak for him in the same breath. When you say “I have not done wrong”, you represent yourself, not God.

So we have two kinds of misrepresentation here. The “I’m right” claim about my status, which shows that my status is in fact wrong, and the “I have not done wrong” claim about my relationship with God, which shows that I am in fact not representing God (but rather in rebellion to him and his word).

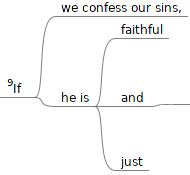

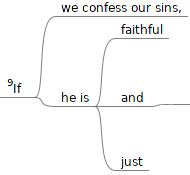

So how does John address these two misrepresentations? This is where we get to v9(a): Again we have an if/then clause, though here the then clause is not about ourselves, but about God. The if clause is we confess our sins, or we agree about our wrongs. This is incompatible with each of “I’m right” and “I have not done wrong”. What is interesting about confession/agreement here, is that God’s truthful position doesn’t change in these three verses. He knows and declares that we are sinners who sin. The only question is, will we agree with him, or will we insist on our own “truth”?

Again we have an if/then clause, though here the then clause is not about ourselves, but about God. The if clause is we confess our sins, or we agree about our wrongs. This is incompatible with each of “I’m right” and “I have not done wrong”. What is interesting about confession/agreement here, is that God’s truthful position doesn’t change in these three verses. He knows and declares that we are sinners who sin. The only question is, will we agree with him, or will we insist on our own “truth”?

If we confess our sins, God is two things for us: faithful and just. These two attributes account for our failures as described in verses 8 and 10. That is, while v8 says our insistence on being right shows that we are wrong, God remains right/just. And while v10 says our insistence that we have not done wrong shows our rebellion against God, God remains faithful to us. So if we have two great desires, to be right and to be in relationship, we fail at each of them when we insist on our own terms. But agreeing with God about our sin results in God’s justice/rightness and faithfulness/relationship to be expressed to us.

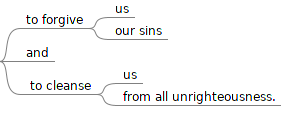

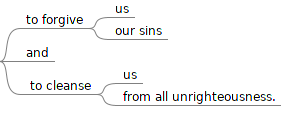

So how is that justice and faithfulness expressed? Verse 9 continues: That is, God’s justice is not expressed only in his wrath against us (as Martin Luther thought before his conversion), and his faithfulness to us is not expressed in simply overlooking our sins (as many people seem to think today). The two things he does to express his justice and faithfulness in this verse are to forgive and to cleanse. Each of these is done to us. But again, we see the binary issue of status and relationship addressed. That is, God forgives our sins, addressing the things we have done. But he also cleanses us from all unrighteousness, addressing the question of our status.

That is, God’s justice is not expressed only in his wrath against us (as Martin Luther thought before his conversion), and his faithfulness to us is not expressed in simply overlooking our sins (as many people seem to think today). The two things he does to express his justice and faithfulness in this verse are to forgive and to cleanse. Each of these is done to us. But again, we see the binary issue of status and relationship addressed. That is, God forgives our sins, addressing the things we have done. But he also cleanses us from all unrighteousness, addressing the question of our status.

So the justice and faithfulness of God come together to make us just and faithful to him, when we confess our sin. I think it is crucial in understanding this, that we accept the following:

- Sin is real.

- Sin is a problem.

- Attaining a desire either to be right or to be in relationship requires solving that problem.

- We cannot solve the problem by simply asserting that it is solved, nor by denying it.

The value of what God promises in v9, then, is that there is an answer to the problem of sin, which avoids denial and proclamation of self-godhood, and which provides for the desired rightness and relationship. That answer acknowledges sin, and it requires us to acknowledge sin, too (v9a: If we confess our sins). Furthermore, that answer addresses the problem of sin directly, by cleaning us from it, and by removing our “unrighteous” status.

So where do we go from here? Based on the above, the first step to fulfilling your desires is to confess your sin, and trust God to clean you off. See his promise of cleanliness as a good thing, and ask him to make you clean. Stop depending on your own efforts to feel good about yourself; admit your denial, self-worship, and rebellion, and ask God to make you right and in relationship with him, as only he can.

A bit of a post-script: as I think about this passage as applied to my life, I identify with the desire for right standing much more than with the desire for relationship. I find it natural and easy to sacrifice relationship in defense of a just standard. But I know many people who seem to most naturally operate in the opposite manner, sacrificing a just standard for relationship. You may be one of them. But the good news for each of us is that in Christ, we don’t have to pick either justice or relationship; we get both. I get the confidence that God cares about my natural bent, but also the correction that his will for me includes not just my natural bent, but much more.

But seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness,

and all these things will be added to you.

(Matt 6:33 ESV)