One of the purposes of going to Cameroon this march is to attend the second “National Symposium on Cameroonian Languages”, at the University of Dschang, in Dschang, Cameroon. I assume it may not be obvious to you why this is a good thing, so I’ll lay out some of my thoughts on linguistics conferences here.

First of all, recall that I am a missionary linguist. That is, I am a missionary and a linguist, something like a missionary pilot is a missionary and a pilot, or like a missionary doctor is a missionary and a doctor. And I challenge people to see that I am not less of a missionary because I am a linguist, and I am not less a linguist because I am a missionary. One might even argue that these two vocations encourage and better each other —that I am a better linguist because I am a missionary, and that I am a better missionary (at least in some ways) because I am a linguist. I love that I get to analyze languages, serve minority (and therefore disadvantaged) peoples, and glorify God, all in one job. The work I do today helps people to read better, which helps their lives today. But it also gives them more powerful access to the scriptures, which provides “value in every way, as it holds promise for the present life and also for the life to come.” (1Tim 4:8b ESV)

So how does my work as a missionary linguist apply at linguistic conferences? I have been tempted in the past to look at conferences as a massive information dump, and I think some people do look at them that way. But one obvious (yet astounding) observation I’ve made about conferences is that they are full of people. And they’re run by people. People presenting, people listening, people asking and answering questions. So whatever else is true of linguistics conferences (local, national, or international), they are an occasion for lots of people with similar interests to get together.

Which doesn’t mean that I man a booth at the side of the food court reading “come to know Jesus through linguistics”. Rather, I get to practice what Jesus teaches me about getting along with people, among perhaps the most secular crowd of people I ever interact with. There are people who are ornry and disagreeable. There are people that don’t know yet how little they know about something. There are people who know more than I ever will about something, and who have no interest in relating to mere mortals as myself —though most people I meet at these conferences could be described as “people”, without stretching the imagination much. :-)

I was at a conference a few years ago, where I had a particular opportunity to show compassion to another person there. It was an international conference, but hosted at a particular university in an African country, so lots of people from that area were able to come. This means that there were people who came from other African countries (like me), people who came from America or Europe, and people who came to the conference without using a passport, all at the same event. At one talk, the speaker used some words in a way that was initially at least confusing, if not just plain wrong (about a fairly basic concept that most people at the conference would be expected to know). I was not alone in this opinion; others asked questions afterward, trying to get the guy to clarify what he meant. They went around a couple times, but eventually they gave up on him, with a response that might be translated “he’s nuts.” Time for questions was up, and we were on to the next speaker, and people cut their losses.

But other missionary linguists and I caught up with him later, and asked him to explain himself more privately. It turned out that he was using a particular theory of a particular linguist that had been published, but that almost no one had heard of. And apparently he was using those words correctly within that theory, but that wasn’t enough to help us understand him without this much longer conversation. In the end, we were able to explain to him that the theory he was using wasn’t known or used many others, so he should either use more standard terminology, or else explain very clearly that he was using these words differently.

But the more important message, to me, was that we cared enough about him as a person (and as a linguist) to follow up with him, and help him get his thinking straight. It cost more time and energy than writing him off when his presentation didn’t make sense (even after questions), but it was worth better understanding him, and helping him be better understood. This idea is part of a core goal of my work: mentorship. That is, I want to have alphabets and writing systems done, so people can read (see above!), but if I can do that, and at the same time train up others to do this work, then I multiply myself, and the work gets on better and faster.

So while an introvert like me is certainly tempted to take every 15 minute brake I get for myself, those breaks are often taken up by processing things with people I know, and getting to know others that I don’t. And often all that rubbing shoulders yields unexpected results.

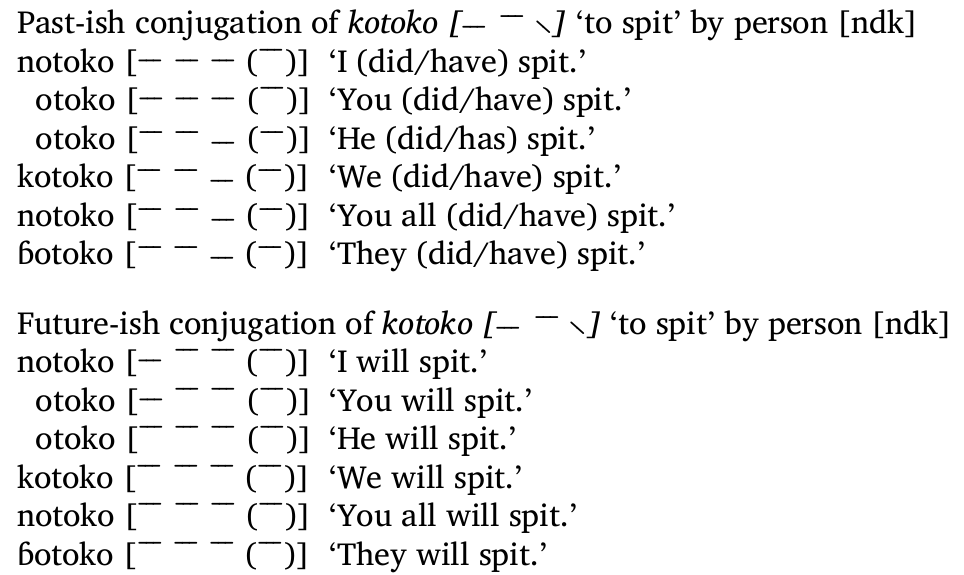

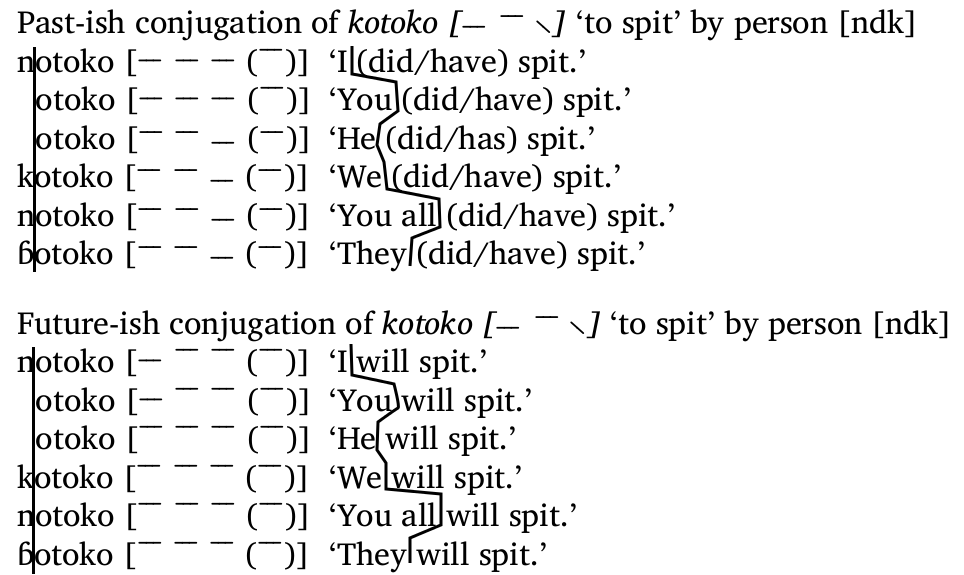

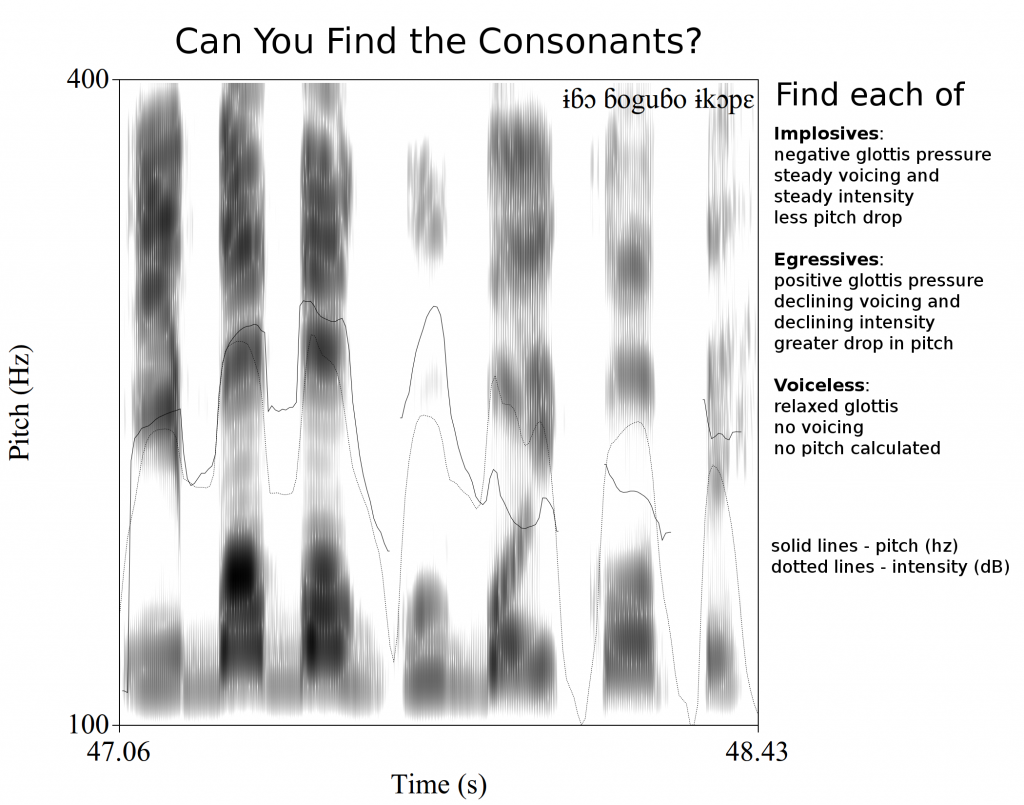

At the last conference I went to (in the US), there was a team of linguists from Ghana (IIRC), who were trying to analyze a tonal language (what I do), but without any particular training or orientation. I was able to point out Tone Analysis for Field Linguists, by Keith L Snider (full disclosure: he was on my committee), probably the most helpful and practical approach to doing tone analysis. And I was able to sit and do some actual acoustic analysis with them. That is, they got out their computers, and showed how they were looking at the speech stream in their recordings (as I described for consonants here). Because all those lines and differently shaded areas require interpretation, and because good interpretation requires experience, I was able to give them some pointers to help them see their data in a more helpful way. It took maybe an hour altogether, but it was time well spent to help someone get along better in this work, and to show friendship and solidarity as well, and that in Jesus’ name.

Anyway, because of the prejudice against Christian missionaries common in most linguistic circles I’ve been in, any time I can show people compassion, care, and honest friendship is a win, even if just a PR win (people know who I work for; it’s on my name tag). But it isn’t just people thinking better of Christian missionaries, or of the church generally. I also get to mix friendliness and compassion with excellent academics (well, I try anyway :-)). So every chance I have to help someone think more clearly, or present his ideas more clearly, or understand someone else’s ideas more clearly, is a chance for people at the conference to see that Christians worship the Truth (John 14:6). Not that everyone receives this, of course: “But let none of you suffer as a murderer or a thief or an evildoer or as a meddler. Yet if anyone suffers as a Christian, let him not be ashamed, but let him glorify God in that name.” (1Peter 4:15-16 ESV)

So regarding this upcoming conference, there are two kids of relationship to build. One is with my expatriate colleagues, other missionary linguists like myself. I know some of them a bit, but most not at all. So it will be good to interact with them through the conference, to enable better collaboration down the road. The other kind of relationship to build is with national linguists, whether they are involved in Bible translation movement or not. I anticipate my work in Cameroon including relationship with government and university entities; this work can only be helped by knowing and being known by Cameroonian linguists. And for those that are still in training, there is a great opportunity to come alongside them, and encourage them in ways that will facilitate more mentorship down the road.

Anyway, I look forward to this opportunity to glorify God by seeking truth and loving people in a way that I am particularly enabled to do, and in a way that will amplify our effectiveness in facilitating local Bible Translation movements throughout the central African basin.