One of the side benefits of the consultant conference I attended in September was that it was in Thailand, where some of our colleagues are based. Specifically, those who work on WeSay, a program I have put to good use in DRCongo, and hope to continue using in Cameroon. The same group also works on non-roman scripts (Writing Systems Technology). Anyway, I got to greet them face to face for the first time, having corresponded with some of them for more than a decade.

One of the highlights of that visit was seeing different font and printing issues they had faced. As I work in writing systems development, this was particularly interesting to me. They work on a different end of the puzzle, though: I work on figuring out what are the consonants, vowels, and tones in a language, and how to represent them well in writing (#FluentReadingMakesPowerfulBibles). This team works on how to take a developed writing system and represent it well in a (unicode!) font for printing.

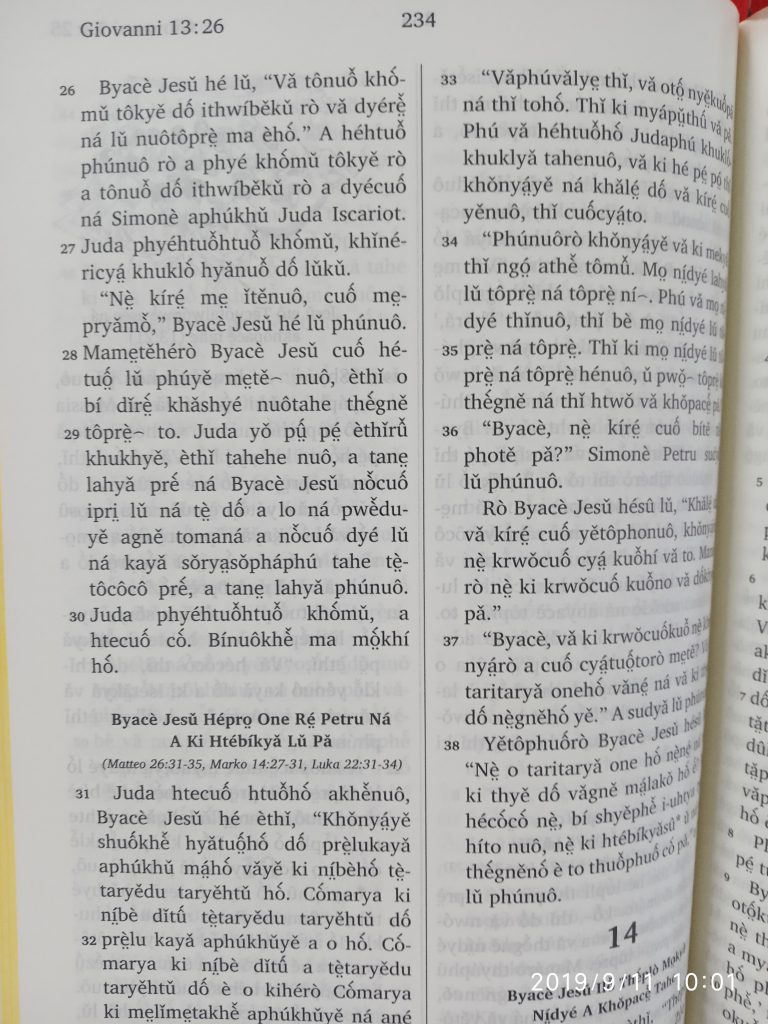

They have examples of printed Bibles with roman scripts (like our letters, though with additional signs for additional vowels, tone, or other important language features):

Even though this script is based on the same alphabet as English, you can see that there are some potential problems for typesetting it. For instance, in many places there are two distinct marks (diacritics) above a vowel, what we call “stacked diacritics”. For instance, in John 13:26 (the first verse on the page) Jesus’ second word “tônuô̌” has two different marks on the final vowel. I assume the one marks a vowel difference (i.e., “o” and “ô” are not the same vowel —like English “bet” and “bit” aren’t the same vowel), and the other marks a difference of tone (i.e., “o” is not the same tone as “ǒ” —like English “convict” (n) and “convict” (v) don’t have the same stress).

When you put these two together, and you have a potential conflict. In my browser anyway (and maybe in yours) the word “tônuô̌” has two diacritics (from ô and the ǒ) typed more or less on top of each other, rather than the diacritic on ǒ being placed above that on the ô, as it should be (and as in the printed Bible). If you scan through that page, you can see lots of variations of these stacked diacritics, meaning its is important to get this correct for printing.

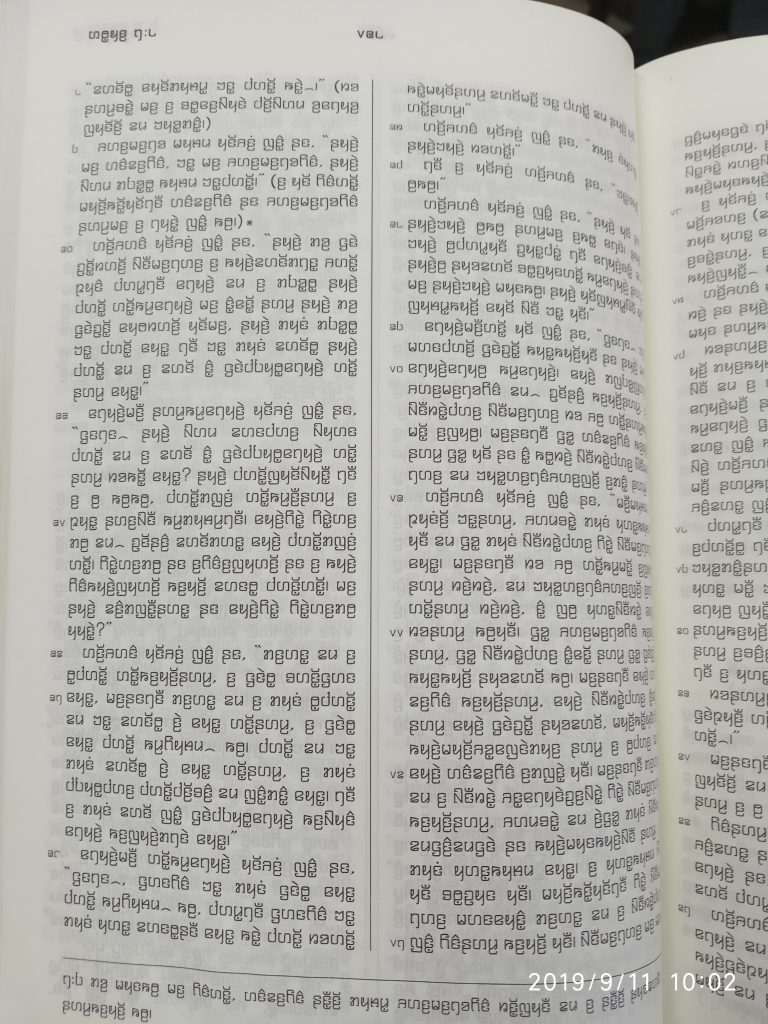

But they also work with non-roman scripts:

These scripts have their own issues, though I haven’t gotten into them myself, since most African languages I have worked with use roman scripts.

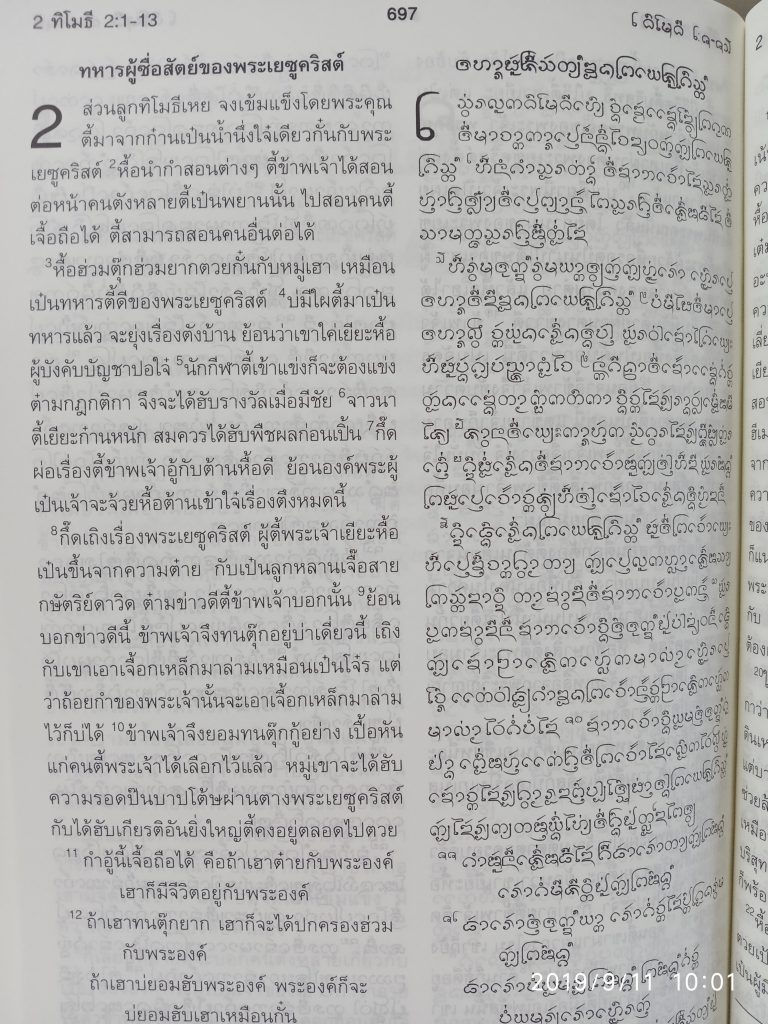

One interesting issue they had to deal with was multiple scripts for the same language. In this example, there was a script of high cultural value, which was not really understood by much of the population. So they wanted to print the valuable script in parallel with the script that people could actually understand:

On some occasions, they have dealt with two (or three) scripts for the same language because it is spoken in multiple countries, and each country as it’s own mandated writing system. Converting checked scripture between these poses its own set of problems.

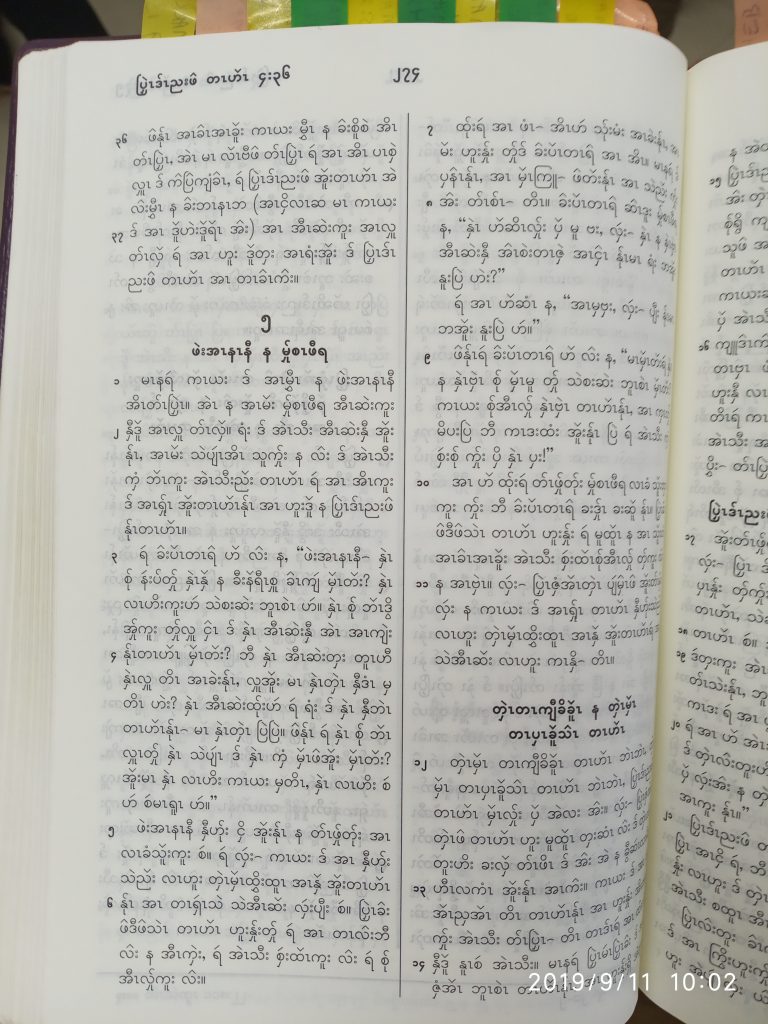

Here is yet another script:

I don’t remember the details of this one, though the tabs a the top of the page each indicate a problem that needed to be fixed in terms of the printing of the writing system. How one writes is typically very important, both to individuals and people groups, so we want to be able to move past making mistakes if possible —though imagine checking the typesetting on this Bible!

Often the two books that help clarify and preserve a writing system are the Bible and a dictionary, which is why we want to get the work done on the writing system early, before we do a lot of printing of scripture portions. And it is again why I pair my dictionary work with writing system development, so people can see lots of words in writing, and give us feedback on problems with the writing system, whether they are technical or aesthetic.

This hard, technical work in advance is worth it because we want the scriptures to be used, and to speak with power into the hearts of the people who read and hear them read. For this to happen, the writing system needs to be acceptable and valued so people will use it, but also accurately reflect the language, so people can use it fluently. #FluentReadingMakesPowerfulBibles