As we mentioned before we left, one of the main goals of our March trip to Cameroon was attending the second National Symposium on Cameroonian Languages (NASCAL2). It was good that we could schedule the trip to coincide with this conference, as this is part of a significant goal for my work: interacting in national linguistics conferences. Because this conference was held some six hours by road north of Yaoundé, it took some work getting there, which I’ve chronicled here.

This is the view out my hotel balcony:

Arriving on time, we had lots of time to stand around waiting for things to begin:

This is what the plenary room looked like for the first couple hours:

This gave me a number of opportunities to meet people, such as Joseph, a professor in the German department in Yaoundé:

But eventually everyone got there, and the first plenary sessions got going:

I was somewhat surprised to see the style of journalism that I had assumed was unique to DRC, recording the presentations:

Unfortunately, the delay starting wasn’t particularly well accounted for in the schedule, and was complicated by power being cut just as the sun was going down, making light even more necessary:

Since most presenters depended on a projector, the room I was in quit for the day, in consultation with the organizers. But this decision wasn’t coordinated across the conference; at least one other room was still going a couple hours later:

So we got dinner and headed back to the hotel, to prepare for the next day:

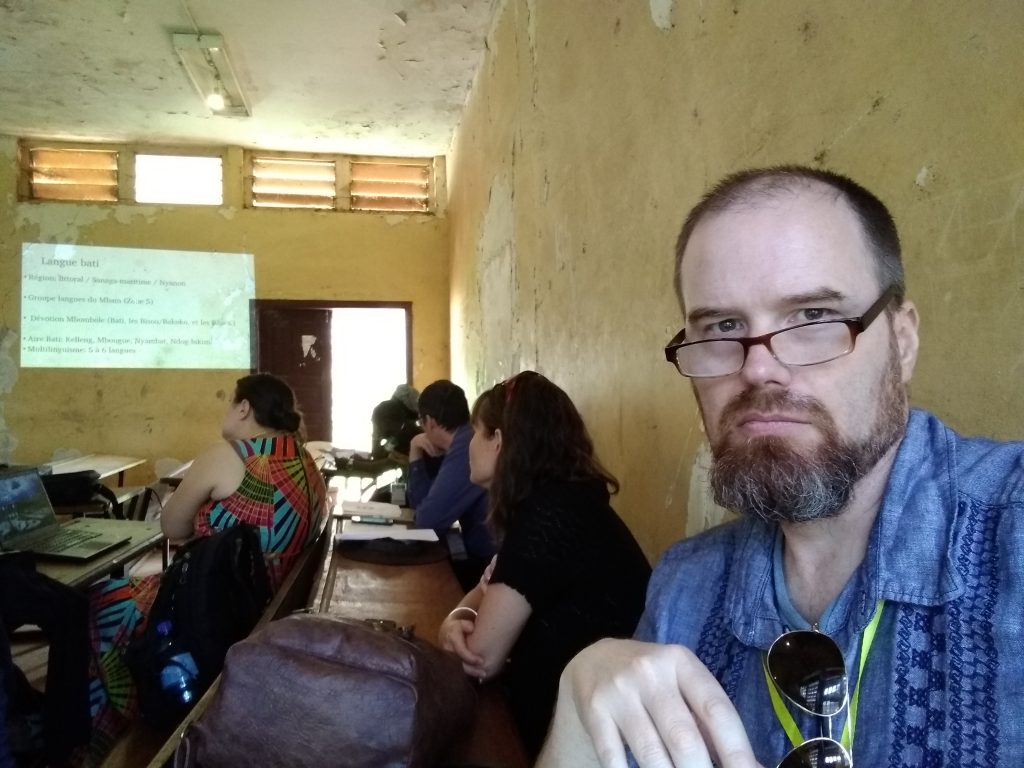

The next morning, we were back in the same room, but with power on (and an adjusted schedule):

I got to hear presentations from other missionary colleagues, like Sarah:

As well as from Cameroonians like Adriel (another doctoral student at Yaoundé)

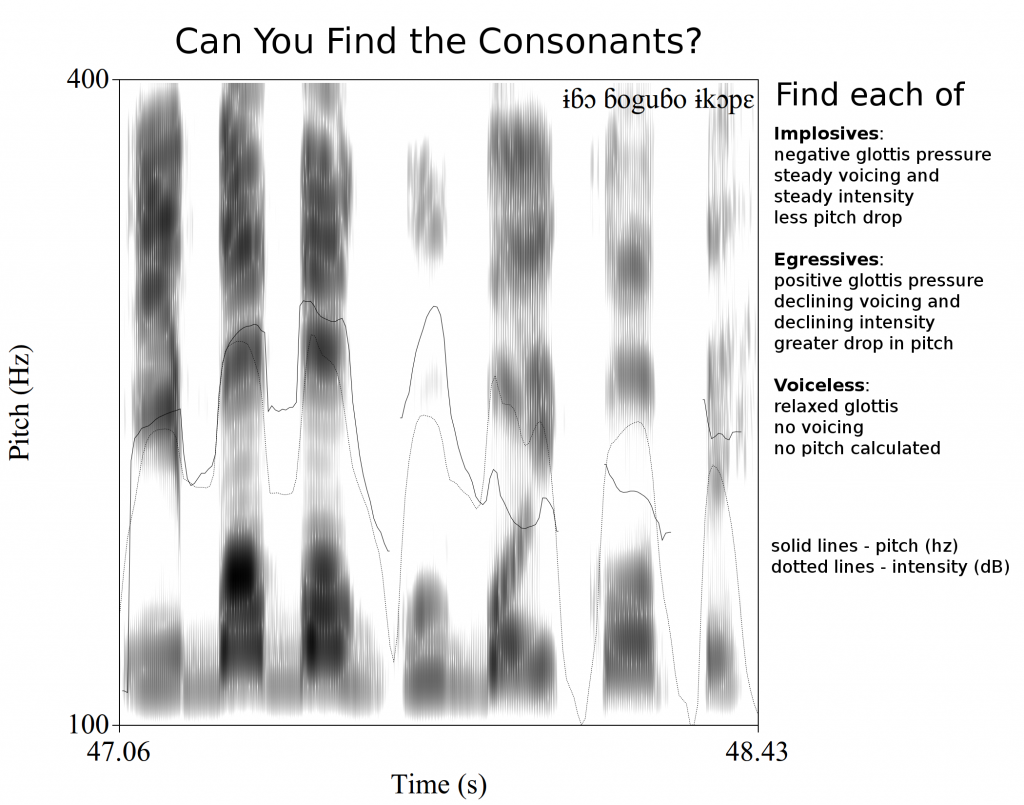

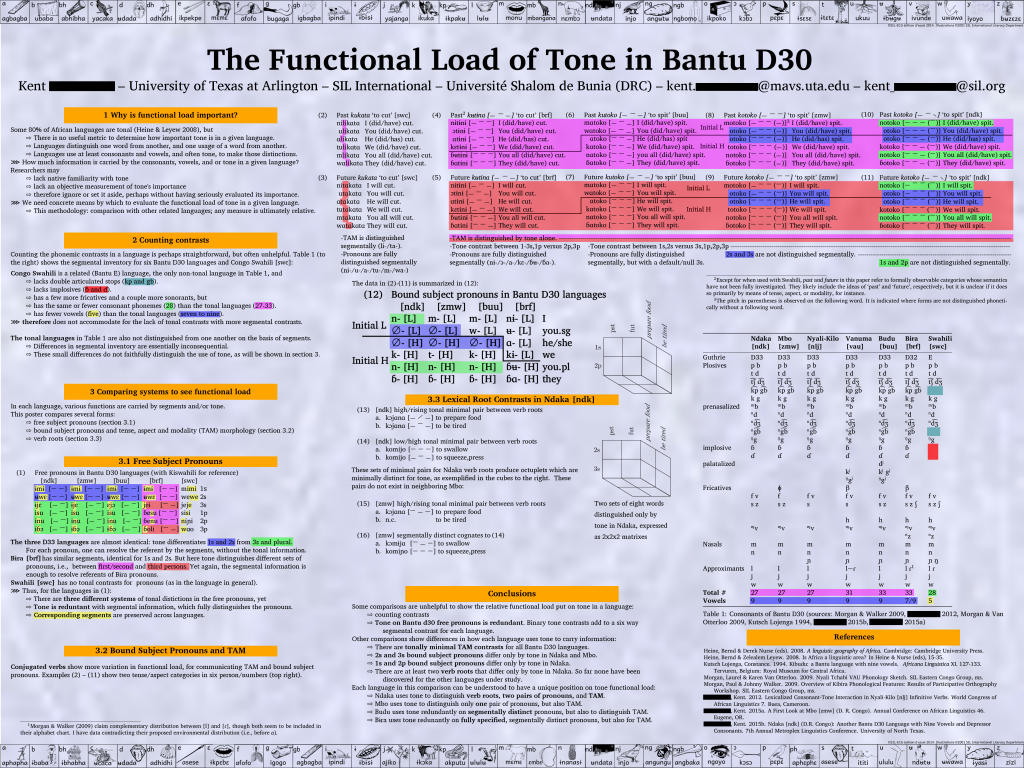

I even got to make my own presentation (on how to evaluate the importance of tone in a given language, which sparked a decent conversation):

There was also more time for side conversations with Joseph Bushman:

and Ayunwe, a professor at the University of Buea (which hosted WOCAL7):

And I got to help out with a group photo for people working with CABTAL (Cameroon Association for Bible Translation and Literacy, a member of the Wycliffe Global Alliance), plus a friend or two:

And I got to speak briefly the with Mathaus, the head of linguistics for CABTAL:

and with Adriel Bebine, who is working on his doctorate at the University of Youndé I (we also got to sit together over the closing meal, so we got to chat some more):

There were lots of corridor conferences with the organizers:

and there were a couple local performers, though I only got a pic of this one:

In the end, we had the obligatory ceremony, wherein I got a certificate confirming my participation (:-)):

After the closing ceremony, and the closing meal (which I guess I didn’t get pictures of!), we headed off to see the local attraction “Museum of Civilizations”:

though on the way I ran into Jeff, a student at the University of Dschang, who gave a loose-fitting shout-out to the Pacific Northwest:

Here is the museum, across the lake in blue:

The lake itself is a fairly major feature of the area:

I have lots of pics of the museum itself, but I won’t spoil the surprise, in case you might go there yourself some day (:-)). They were very proud of it, and kept it open late to allow us to see it.

So over all, the conference went well. The organization did not allow as much time for informal interaction as I’m used to having (between presentations, over meals, etc), but I did get to make a number of introductions, which was much of what I was hoping for. On the way home, I texted with one contact I’d made about the possibility of helping with some teaching on tone, which would be a strategic way for me to use my training. So we got some relationships started, with those currently in and out of Bible translation work, and with people in universities and in other institutions. As we make our move to Cameroon this June/July (Lord willing!), we’ll be able to further cultivate these relationships, and see how we can best help the church and Bible translation movement in Cameroon!