It doesn’t make sense on paper to uproot a teenager for the final year of school. But we were questioned about taking him to France as an infant, or to Congo as a kid; much about our life looks like foolishness to some people.

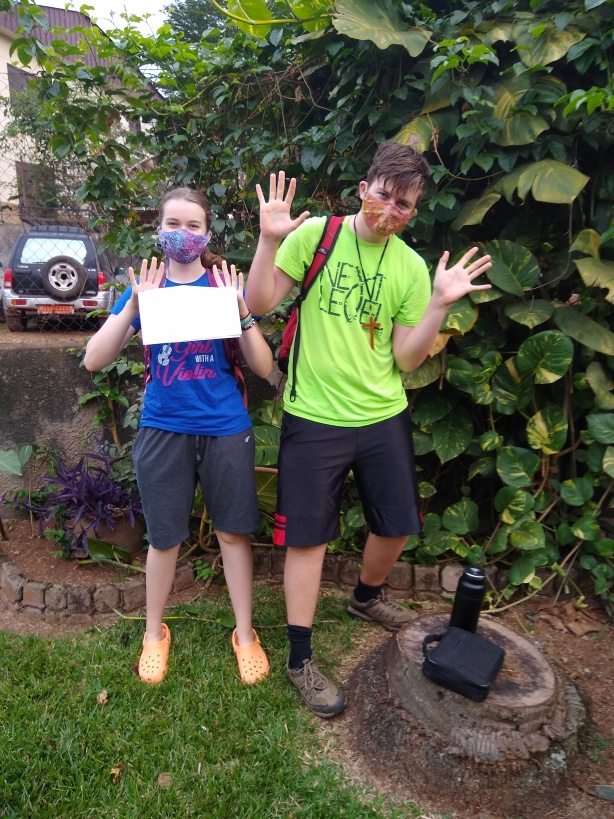

But there are a number of reasons why it makes sense for us to go to Cameroon at the end of this school year, including the fact that Anna will be starting junior high, and Joel will be starting high school.

But James will be a senior next year, and the school in Cameroon has a policy of not admitting students for their senior year only. We believe this is a good and reasonable policy. However, we also think is a good and reasonable thing to ask for an exception to this policy for James. In this post, I’ll discuss some of the reasons their policy makes sense, and why we think James will do OK.

The policy makes sense

Teenage years are tumultuous enough already, without adding a change of school (not to speak of country and language). I know; I moved high schools after my sophomore year. The transition to a new school wasn’t easy, with new classes, new class requirements and prerequisites. I made the best of it, but I wasn’t changing languages or countries (unless you count California to Oregon as an international move.… :-)).

Added to the above are the transitions particular to life in a cross-cultural context. The school is in Cameroon, which has its own cultures, languages and politics. Language might be the easiest to deal with, since French is a national language in Cameroon (in addition to English). But needing to use French to take a taxi, or to buy or sell in a marketplace, is a different kind of stress than having to take a language class.

Politics in Cameroon is its own thing, perhaps especially right now. I hear (from Cameroonians) the president has been in power for a long time, and many people hope for change. There is talk of succession from the provinces that use English, to the point that at least some expatriates are not living there now. When we were there in 2004 (just after Joel was born), I recall the particular irony of not seeing any campaigning for the presidential election until after the election took place.

Encountering other cultures is one of the mixed blessings of any cross-cultural context. We get to rub shoulders with other brothers and sisters in Christ before we meet them at the throne of God (Rev 7:9̈-10). That said, other cultures have other foods, customs, and expectations of life, and these can take some getting used to. My personal top two “I hope I never have to eat that again” foods (tadpole soup, and fermented manioc) were first encountered in Cameroon, though we also saw fermented manioc in D.R. Congo. These adjustments are not insurmountable, but they do take time and work to deal with.

So when you add changes in language, culture and politics to changes of school and hormones, we get that this is not a small task, and we understand why many students would isolate themselves, come to hate themselves or their new context (or their parents, or God), and ultimately do very badly in a single senior year abroad.

James will do OK

That said, we believe that James will do OK, by God’s grace.

As I have talked to people who survived having missionaries as parents, and as I talk to people who work with missionary kid issues, it seems like one of the biggest indicators of how a missionary kid turns out is how much a part of the mission the child personally feels. Because of this, we have for some time talked our kids through transitions from the perspective that this is something our family is doing together for one purpose —not that dad has a job change and everyone else has to go along.

Another key element in weathering transition well, I find, is talking through transition, before, during, and afterward, to make sure everyone is processing it emotionally. This was a particular issue as we struggled with the more difficult years of Asperger’s, but we got used to talking each of our kids through what we would do when and why, so when we did it, there were fewer surprises for them. As soon as we would have an itinerary, we would talk about which planes we would take where (including which would have bathrooms, and which would have movies). I’m not saying this is something we have perfect, but we as a family have lots of experience weathering transition —enough to feel when things are going well, and when we need to take more time to work through things.

The above has two caveats. First, our kids have mostly been in Texas the last five years. So while James remembers Africa, I’m sure he will be surprised more than he thinks. Second, all of this (as in all things) has been done by God’s grace. When I say “experience” above, what I really mean is having some information in advance, but still screwing things up, and depending on God to make things right. Then spending time processing what happened and how to do better. Which means we have more information for the next time, but we still screw things up, and still need God to work all things to good (Romans 8:28). So ultimately what I mean by saying “James will be OK” is that God has given us a history both of weathering transition, and of depending on him, and we trust that he will show himself to be good in this case, as well.

What does this look like practically, right now? We are nine months out from a potential move to Cameroon at the end of this school year. We have already had a number of conversations, both as a family and individually, about the cost and the value of this transition. I have asked each of us to spend some time considering what the cost and value are for us personally, and we’ve had a number of very productive conversations since then. My goal is that each of us would have bought in to this transition without reservation —well in advance of any family move.

So far, I’ve talked more about our family process than about James. There are also a number of reasons why I think James will handle this transition well —beyond the fact that we have experience processing these things as a family. Basically, James is doing well in school, better than we imagined he would five years go. He takes tests very well, and he has developed friendships with classmates that he wants to see outside of school (something I never did much of in high school ;–)). But despite learning to be social, he is excelling at honors and college prep classes in almost every subject, including AP English; he is taking calculus now, as a Junior. James is in his fourth year of French now, and seems eager to be able to use it. Despite wanting to study math in college, he is also working on an endorsement in engineering. And until recently he insisted on taking (and enjoying, and doing well in) art —something I never managed to do myself.

Outside of school, James has showed a commitment to piano, both in practice and lessons (currently working on Sonata in G Major), and in leading worship at church. He is a very emotive pianist, and has said that playing the piano helps him express feelings that don’t come out in words. His commitment can be seen in that he wakes up at 5:45am to practice before school each day.

I’ll let James himself speak to his own motivation to go to Africa for his senior year (post coming soon), but I am grateful for the growth, maturity and responsibility he’s had to date. I am more grateful to see the man God is making him – especially given where he’s been.