I never met a woman named Peninnah until I lived in Africa. I recall first hearing this name, mostly because it was so strikingly novel that I assumed it was a mistake, and had to ask her name again. Even my spellchecker doesn’t recognize this name. But since that first one I met in the year 2000, I’ve known several —but all in Africa.

I found the above particularly interesting, given that it is a Biblical name. People like naming their kids after heroes of the Bible. So why are all the Peninnahs (that I’ve known) in Africa? Why don’t we name our daughters Peninnah in the US? A look at Peninnah’s story sheds light on this, and helps us know a bit more about Africa, and about the promises of God.

She is introduced at the beginning of 1 Samuel 1 (all ESV) :

[Elkanah] had two wives, one named Hannah and the other Peninnah. And Peninnah had children, but Hannah had none. (v1)

An exhaustive search of the Bible yields only four references to “Peninnah”, all in 1 Samuel 1:2-6. We know that she was loved and cared for by her husband:

And whenever the day came for Elkanah to present his sacrifice, he would give portions to his wife Peninnah and to all her sons and daughters. (v4)

But as might be expected in a polygamous household, there was not equal love and care for the two wives:

But to Hannah he would give a double portion, for he loved her even though the LORD had closed her womb. (v5)

So we see that Hannah has more love and care from her husband, but Peninnah has children. Naturally, these two wives of Elkana did not get along:

Because the LORD had closed Hannah’s womb, her rival [Peninnah] would provoke her and taunt her viciously. And this went on year after year. Whenever Hannah went up to the house of the LORD, her rival taunted her until she wept and would not eat. (vv6-7)

So one might say that Peninnah was not a particularly nice woman. This may have come in part from her husband loving his other wife more, but in any case, she made Hannah’s life miserable.

In terms of understanding the scriptures, Peninnah is perhaps most helpful to us as a contrast with Hannah, who later gives birth to Samuel. Interestingly enough, I can’t recall ever meeting an African Hannah. But 1 Samuel gives us a lot more information on Hannah. Her character is revealing in response to her co-wife’s taunting:

In her bitter distress, Hannah prayed to the LORD and wept with many tears. (v10)

Her prayers are so moving they are taken for drunkenness. But in the end, the priest of Shiloh looks favorably on her:

“Go in peace,” Eli replied, “and may the God of Israel grant the petition you have asked of Him.” (17)

Whatever might be said of the value of the priesthood of Eli and his sons (e.g., 1 Sam 2:12), Hannah’s worship seems sincere:

The next morning Elkanah and Hannah got up early to bow in worship before the LORD, and then returned home to Ramah. (v19a)

Curiously, Peninnah doesn’t seem to be there at this time. Did she no longer go to Shiloh to worship with her Husband each year? Or was she just written out of the story at this point, as unimportant? Either way, her importance to the story is at least minimized, and there is no Biblical evidence of faithful worship from her at this point (since v4), whereas the importance of Hannah’s faith is paramount:

And Elkanah had relations with his wife Hannah, and the LORD remembered her. So in the course of time, Hannah conceived and gave birth to a son. She named him Samuel, saying, “Because I have asked for him from the LORD.” (vv19b-20)

Hannah prayed for a son, and attributed giving birth to him to God. And in time, she fulfilled the vow she made in v11:

Once she had weaned him, Hannah took the boy with her, along with a three-year-old bull, an ephah of flour, and a skin of wine. Though the boy was still young, she brought him to the house of the LORD at Shiloh. And when they had slaughtered the bull, they brought the boy to Eli.

“Please, my lord,” said Hannah, “as surely as you live, my lord, I am the woman who stood here beside you praying to the LORD. I prayed for this boy, and since the LORD has granted me what I asked of Him, I now dedicate the boy to the LORD. For as long as he lives, he is dedicated to the LORD.”

So they worshiped the LORD there. (vv24-28)

And as if that were not enough, Hannah gives a magnificat-esque song of thanksgiving (in 1 Sam 2:1-10), prefiguring Mary’s song of praise after Jesus met John the Baptist, while each was still in the womb (in Luke 1:46-55).

So we see that Peninnah and Hannah provide an interstesting clash between what the scriptures elsewhere call children of the flesh and children of the promise.

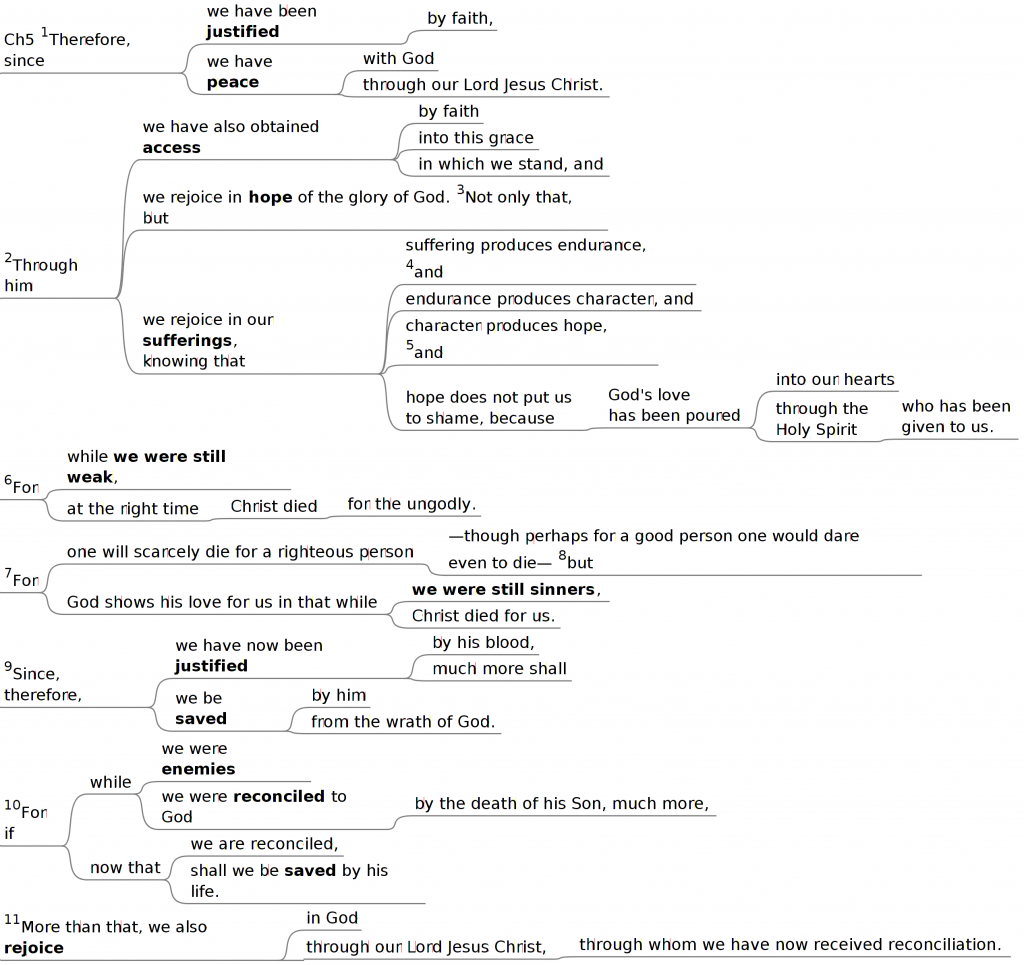

In Galatians, this contrast is described in terms of law v promise:

For if the inheritance comes by the law, it no longer comes by promise; but God gave it to Abraham by a promise. (Gal 3:18)

This is an argument against trusting in the Law, but Paul continues to make explicit reference to children born, either as a result of the power of the flesh (the way children are normally born), or as a result of the promise of God.

For it is written that Abraham had two sons, one by a slave woman and one by a free woman. But the son of the slave was born according to the flesh, while the son of the free woman was born through promise. Now this may be interpreted allegorically: these women are two covenants. One is from Mount Sinai, bearing children for slavery; she is Hagar. Now Hagar is Mount Sinai in Arabia; she corresponds to the present Jerusalem, for she is in slavery with her children. But the Jerusalem above is free, and she is our mother. (Gal 4:22-26)

So Paul says that the children born by the natural power of the flesh are born into slavery, whereas the children born by the supernatural power of the promise of God are born for freedom, for heaven. And just like with Peninnah and Hannah, the two kinds don’t get along:

Now you, brothers, like Isaac, are children of promise. But just as at that time he who was born according to the flesh persecuted him who was born according to the Spirit, so also it is now. But what does the Scripture say? “Cast out the slave woman and her son, for the son of the slave woman shall not inherit with the son of the free woman.” So, brothers, we are not children of the slave but of the free woman. (Gal 4:28-31)

Note that these references are made to the children of the two wives of Abraham (Sarah and Hagar), but the same applies to Peninnah and Hannah. The one bears children by her own strength, and the other, devoid of any such power of her own, bears children by the promise of God.

This principle is found throughout the new testament. The writer of Hebrews talks about the faith of Abraham as a confidence and trust in a specific promise of God:

For when God made a promise to Abraham, since he had no one greater by whom to swear, he swore by himself, saying, “Surely I will bless you and multiply you.” And thus Abraham, having patiently waited, obtained the promise. (Heb 6:13-15)

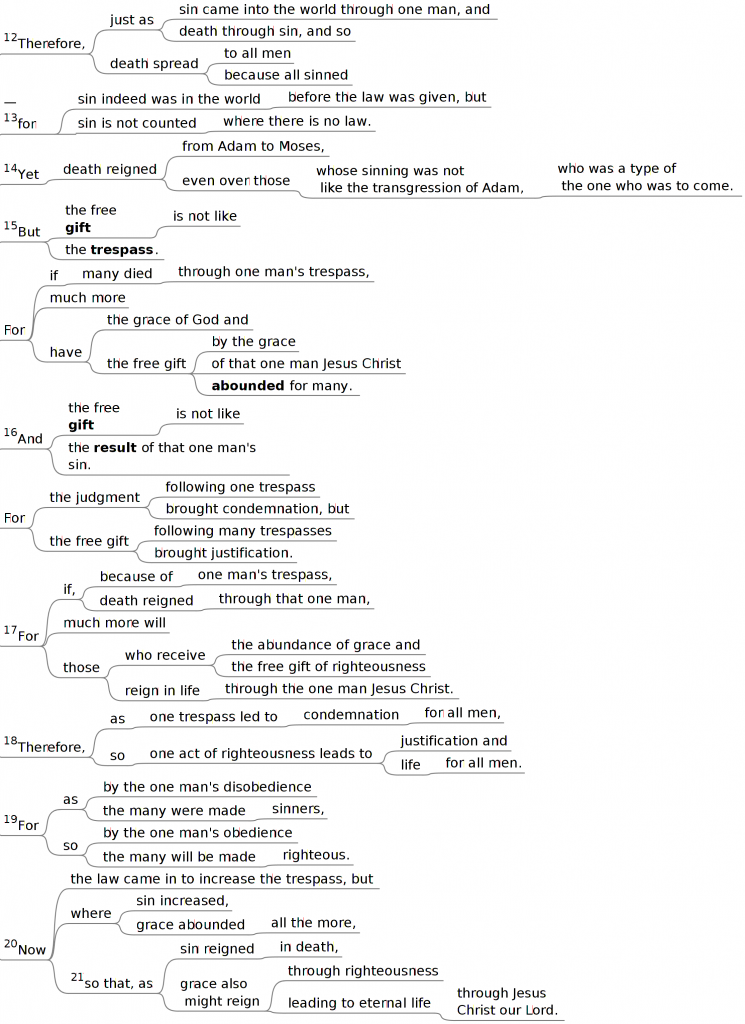

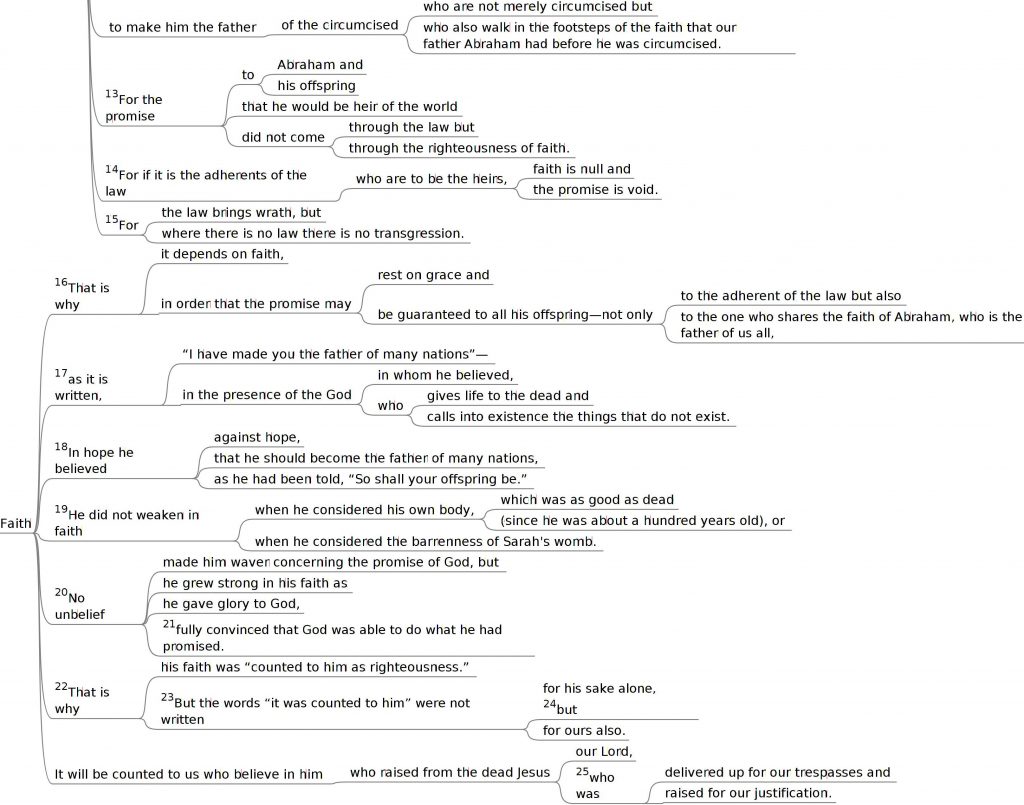

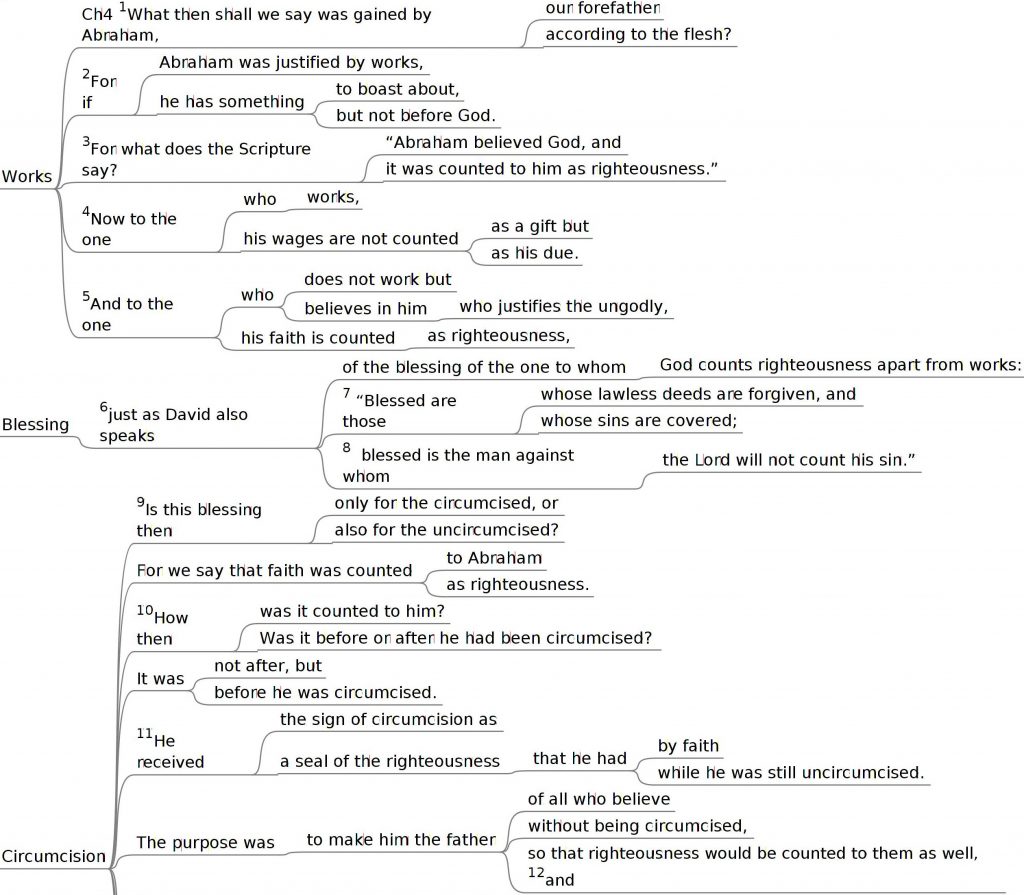

And Paul in Romans contrasts again the inheritance according to the law, and the inheritance according to the promise.

For the promise to Abraham and his offspring that he would be heir of the world did not come through the law but through the righteousness of faith. For if it is the adherents of the law who are to be the heirs, faith is null and the promise is void. (Rom 4:13-14)

I think of it this way. If your father (or someone else you trusted) promised to give you something of great value (house, boat, boathouse, etc), but it you were concerned that he might not follow through, would it make sense to take him to court over it? To go before a judge and insist that you have a legal right to have a personal promise fulfilled just doesn’t make sense. Rather, if a person has promised something, you can address the fulfillment of that promise on the basis of that personal relationship. Unless, of course, your objective is to ditch the relationship and wrangle what you can from the person by force. Good luck trying that with God….

As I think about the promise(s) of God, it helps me to ask what specific promise(s) we’re talking about. This is because I think people can get fuzzy in their thinking, and think of general “promises” without really having something in mind. Whereas I think God has made specific promises which I think are good for us to trust in, just as we commit specific sins of which it is good for us to repent. Romans 9 gives us a very important clarification of (at least one) promise to Abraham, with its relation to election and the salvation of a remnant, as opposed to the whole:

But it is not as though the word of God has failed. For not all who are descended from Israel belong to Israel, and not all are children of Abraham because they are his offspring, but “Through Isaac shall your offspring be named.” This means that it is not the children of the flesh who are the children of God, but the children of the promise are counted as offspring. For this is what the promise said: “About this time next year I will return, and Sarah shall have a son.” (Rom 9:6-9)

So the promise was the supernatural birth to Sarah, a 90+ year old woman. For this passage, it is importantly not the natural birth to Hagar, a much younger and more fertile woman. And these two births distinguish between two lines of descendants of Abraham. And So Romans 9 shows “the word of God has [NOT] failed”, because the promise of salvation never was to all Abraham’s descendants, but rather to his descendants by the promise to Sarah.

In the same way, as we look at “all Israel” later in history, we see that not all are saved. But the promise of God never was that each individual would be saved. Rather, those who are born of the promise will be saved, and those who are born of the flesh will not. Jesus says it this way:

Jesus answered him, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born again he cannot see the kingdom of God.… That which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit.…” (John 3:3,6)

So those of us who are born again, who are born of the Spirit, according to the promise of God, will see the kingdom of God. Notably, those whose inheritance derives only from the law, or from their own strength, will not.

To me, this is a very sharp criticism of the “self made man.” American culture is full of the ideal of managing everything by our own strength, of never depending on anyone else. I think it is good to be responsible, and to attend to our daily needs without excessively burdening others. But the clear teaching of scripture is that it is the one who depends on the promise of God, not his own strength, who is approved by God.