I was asked this question in our home group recently, after a larger discussion on church discipline, and forgiving the repentant. I found a large number of documents online with various opinions. I read through the first nine that showed up on a google search, and summarized their positions below. I found it interesting that this question, like many questions, didn’t have two answers to the same question, but rather two answers to two different questions. That is, these sites don’t so much differ on whether we should forgive the unrepentant, but on what forgiveness means, and/or how God forgives (conditionally or unconditionally).

How does this happen? There is a cool word we use in linguistics that will help us out a lot here: polysemy. Poly is many, and sem is meaning (and -y is the condition), so this is the condition of a word or phrase having multiple meanings. This can cause us problems when we don’t recognize it, because one person may use a word in one sense, and another person may use the same word in another sense, and they may not even realize they’re using the word differently. I deal with this in Bible study a lot, where two different verses or passages may use the same word with different meanings; if we don’t recognize this, we may think they are contradictory, or in some other way saying something they aren’t.

One classic case of polysemy is “the law”. When reading this phrase in the Bible you really must ask yourself, is it referring to:

- The Mosaic Law, i.e., the set of laws given to Moses

- Another set of specific laws, given to someone else, e.g., Adam, or Noah

- The Pentateuch (first five books of the OT), e.g., “the law and the prophets”

- Moral principles in nature, e.g., the natural law

- Moral principles known to individuals subconsciously, i.e., conscience

- Any set of principles that describes behavior or action, e.g., scientific laws

- Or some other written or unwritten code or principle.

I hope it is evident that when you read “the law” as referring to one of these, when the author intended another, there is bound to be misunderstanding.

In final defense of polysemy (in case the above does not pursuade you), I would refer you to any dictionary of quality. Almost every word in a good dictionary has multiple senses/meanings, usually indicated as in the following: “chair: 1. a separate seat for one person, typically with a back and four legs. 2. the person in charge of a meeting or organization (used as a neutral alternative to chairman or chairwoman).”

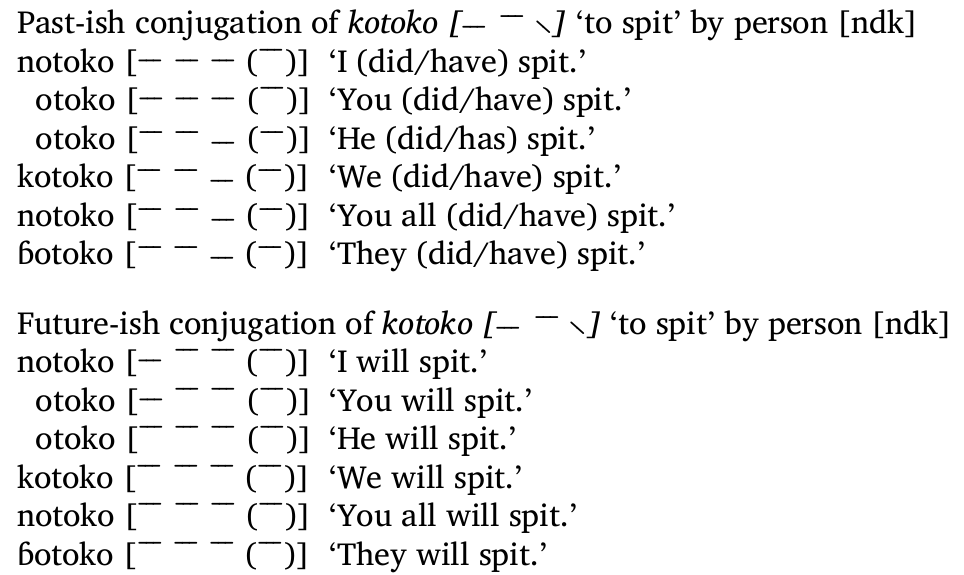

So what is forgiveness? Looking at these websites (as a good descriptive linguist would of course do), it is clear that forgiveness is being used in at least two distinct senses:

- Giving up a grudge against someone who has sinned against you.

- Declaring and/or acting as if a particular sin is no longer an issue.

Closely tied to these is a third that also occurred on occasion:

- reconciling relationship between offended parties

Before addressing the above, I would like to consider another point that occurred frequently on the “Forgiveness conditional on repentance” camp, AKA the “Forgive as God Forgives” camp. This side claims that God doesn’t forgive the unrepentant, so we shouldn’t. This is in the legal sense of the presence of sin, not the maintenance of a grudge. But is this the case, even legally? Does God have a PRE-condition of repentance before he forgives? I think it is Biblically clear that repentance and forgiveness go together, but I don’t know that the one must precede the other. In fact, insisting that we repent before God forgives us is tantamount to saying that we must become alive (c.f., Eph 2) before God can give us life.

To put it otherwise, a precondition of repentance is a works based righteousness, claiming that we have forgiveness because we have done the work of repentance. Rather, as our Lord said: “You did not choose me, but I chose you and appointed you that you should go and bear fruit and that your fruit should abide, so that whatever you ask the Father in my name, he may give it to you.” (John 15:16 ESV). Or as Paul said, “but God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” (Rom 5:8 ESV) and again “But God, being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ—by grace you have been saved….For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast.” (Eph 2:4,5,8,9 ESV)

But even if you take God’s forgiveness to have a pre-condition of repentance, I think the connection to our forgiveness must break down. For when Paul speaks of the action of God on our behalf across eternity: “And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified.” (Rom 8:30 ESV) we understand that repentance is implied, even if not stated. But that is not a repentance that we come up with on our own, or else Paul’s argument doesn’t work. What would happen if God predestined, called, and justified someone who then refused to repent? Rather, we understand that God’s gracious calling also grants us the grace to repent. But this is not something we can do for others. If someone sins against me, I simply cannot provide him the power to repent. When God effectually desires to save and provide repentance, he does. But we, on the other hand, may well desire repentance and salvation for years, with no apparent change. Should we wait for that?

Some of the people cited below say “yes” to that question. But let’s be clear that they are saying that they will not say that a person’s sin has been paid for until those sins have actually been paid for. This I get, and I respect it so far. But alongside that comes a temptation, I think, to hold a grudge. And this is where the polysemy above is important. Almost across the board, answers to this question have affirmed that we need to be willing to forgive. I think this is essentially one thing under the sense of giving up a grudge. Whether or not someone has a debt in their account with God, we simply cannot go through life blocked by that fact. On this point modern psychologists and Biblical scholars agree.

One point that has come up multiple times is to consider the alternative: will we really withhold relationship from everyone who has not explicitly apologized to us? If so, how would we ever get anything else done? Do we want to be held captive by the millions of peccadilloes we suffer each day?

In any case, it is clear that this willingness to forgive should be there before repentance:

- “And Jesus said, ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.'” (Luke 23:34 ESV)

- “And as they were stoning Stephen….he cried out with a loud voice, ‘Lord, do not hold this sin against them.'” (Acts 7:59-60 ESV)

The ultimate response to this question for me, however, is to consider the meaning of “Forgive as God forgives you”. An important rule of Bible study is to look at the context. Two verses which end with this quote are as follows:

Let all bitterness and wrath and anger and clamor and slander be put away from you, along with all malice. Be kind to one another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ forgave you. (Eph 4:31-32 ESV)

What is this talking about? Is Paul saying here, that we should NOT forgive until the offender repents? Even if he thought that were true, that is not his point here. Put away bad feelings towards each other sounds an awful lot like giving up on grudges, rather than like making sure your sin accounts match God’s. when I think of How God forgives me, lots of things come to mind, which are more relevant to this context:

- God in Christ forgave me freely

- God in Christ forgave me graciously

- God in Christ forgave me completely

- God in Christ forgave me lovingly

- God in Christ forgave me for my good

- God in Christ forgave me to satisfy His wrath

- God in Christ forgave me while I was dead

- God in Christ forgave me while I was His enemy

If you wrestle with the idea of giving up a grudge against someone who has wronged you, someone who hasn’t apologized, I would strongly encourage you to consider your own standing before God. Do you really understand the depth of your own depravity? Do you really understand what it cost Him to forgive you? Do you really think you changed your heart on your own? Do you really think that this other person will do what you didn’t?

And with regard to keeping our accounts in line with God’s: “Who are you to pass judgment on the servant of another? It is before his own master that he stands or falls.” (Rom 14:4 ESV) God is the only and final judge, and He does that better than us, anyway.

Putting these two points together (that we and they must each give account to God):

Why do you pass judgment on your brother? Or you, why do you despise your brother? For we will all stand before the judgment seat of God; for it is written,

“As I live, says the Lord, every knee shall bow to me,

and every tongue shall confess to God.”

So then each of us will give an account of himself to God. (Rom 14:10-12 ESV)

And this is the lesson we teach our kids on a daily basis: deal with your own issues; they are more than enough for you. Fix your side of the problem, before worrying about their side. Or, if you prefer to hear it from Jesus: “first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your brother’s eye.” (Matt 7:5 ESV)

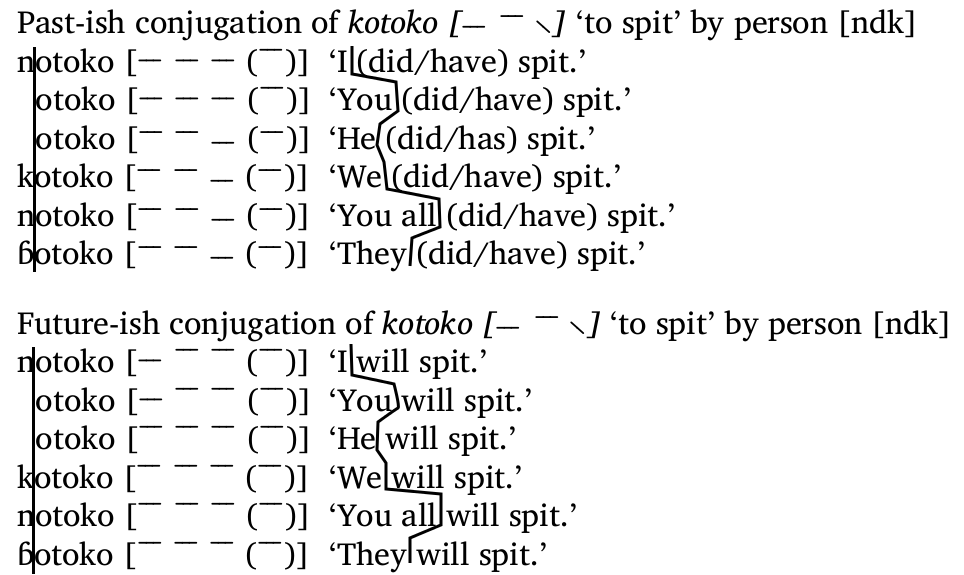

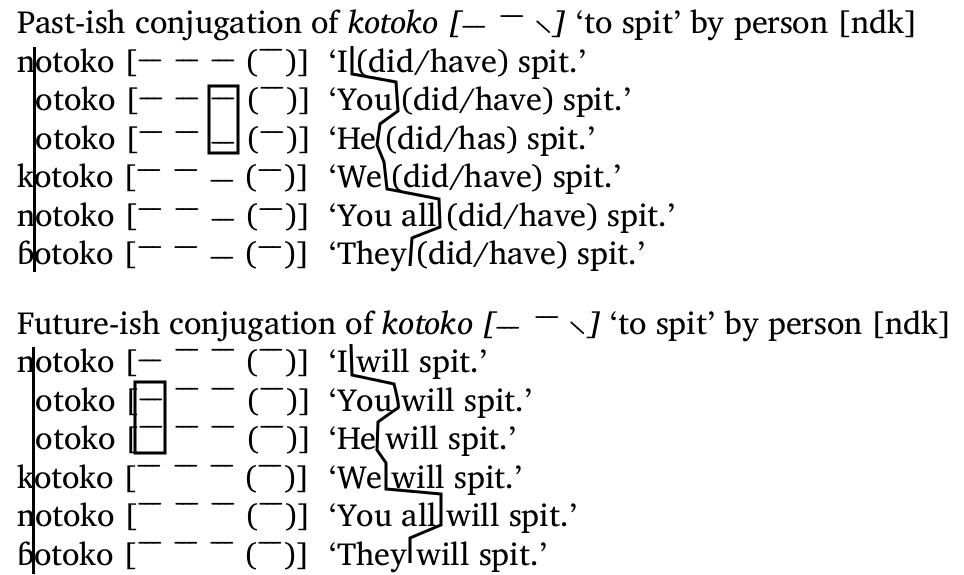

Appendix: Two different questions on Forgiveness

Benefit to the forgiver

Christianity Today: “If we wait for those who have hurt us to repent first, we will almost certainly wait for a long, long time.… Even non-Christian organizations are emerging to show the value of forgiveness; their premise is that the greatest benefit of forgiveness accrues not to the one who is forgiven, but to the one who forgives….One of Jesus’ main teachings was that we love our enemies, pray for them, and do good to those who have hurt us.”

Focus on the Family: “You really have no choice. Either you forgive or you slowly poison your mind and heart. If you hold on to unresolved bitterness it will destroy you.…We offer this forgiveness to others purely in response to the grace we have already received from the Lord. If we are not willing to forgive, it is an indication that we have not fully understood or experienced the grace of being forgiven (see Luke 7:47). ”

Ancientfaith.com: “On a personal level we also find ourselves feeling justified in withholding forgiveness, using our anger and resentment, and the weight of a broken relationship as tools of punishment. …To forgive a brother who repents, works towards our own repentance. To forgive even when no sorrow has been offered in return works an even greater repentance….It is a mistake to become formulaic about forgiveness and repentance, creating rules about what must come first or the conditions required.…The believer who lives waiting to be asked to forgive is dangerously close to the Lawyer who asks, “Who is my neighbor?” He is too likely only to forgive with the measure of someone’s sorrow and learns to hold back what could be given freely. There is a caution in his heart that becomes the enemy of grace and repentance.”

The Gospel Coalition: Recognize that sin goes both ways. Distinguishing (attitude of) forgiveness v reconciliation/restauration (of relationship). Rom 12:18 If possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all.

Forgiveness conditional on repentance (?As God Forgives)

Gotquestions.org: “We need to make an effort to understand God’s forgiveness of us if we are going to forgive others in a way that reflects God’s forgiveness. Sadly, in recent decades the word forgiveness has taken on a connotation of “psychological freedom” instead of freedom from sin, and this has brought some confusion about the whole concept of what it means to forgive.…Forgiveness offered and forgiveness received are entirely different, and we don’t help ourselves by using a catch-all word for both.… First John 1:9 shows that the process of forgiveness is primarily to free the sinner; forgiveness ends the rejection, thus reconciling the relationship….In short, we should withhold forgiveness from those who do not confess and repent; at the same time, we should extend the offer of forgiveness and maintain an attitude of readiness to forgive.”

Questions.org: ” Offering forgiveness without repentance, however, does not follow the biblical model of forgiveness (Luke 17:3,4).…We must recognize our sin and repent to receive and enjoy God’s merciful forgiveness. God requires repentance and so must we.…If we don’t admit our sin, it’s impossible to be transformed.… If as believers we don’t require repentance on the part of the offender, we stand in the way of that person’s coming to see his need for God and experiencing His forgiveness.…It’s wrong, however, to assume that if we don’t forgive someone, we’ll be weighed down with hatred, bitterness, and revengeful desires. That’s not necessarily true because the Bible says we are to love a person regardless of whether or not he or she shows any remorse. We can love our enemies, but continue to have an unsettled issue with them. In many cases, it is more loving to withhold forgiveness until a change of heart is demonstrated than it is to offer forgiveness without the offender’s acknowledgment of deliberate wrongdoing.…Instead of giving in to revenge, we can soften our hearts toward those who have hurt us when we humbly admit that we, too, have hurt others.…The ultimate purpose of forgiveness is the healing of a relationship. This healing occurs only when the offender repents and demonstrates remorse and the offended one grants a pardon and demonstrates loving acceptance. ”

Luke173ministries.org (wrt adult children of abuse): “Biblically speaking, NO ONE gets forgiven without changing his ways and turning to God and godliness.…The Bible does in fact tell us that we should forgive as the Lord forgave us (Colossians 3:13; Ephesians 4:32). But there are requirements for forgiveness. If we read in more depth and in context about God forgiving us, including the hows, whys and under what circumstances, we will see that he only forgives us when we come to him in the spirit of remorse, change our lives through his Son, ask for forgiveness, and repent (CHANGE). So if we are to forgive others as God forgives us, then we are to forgive them AFTER they have shown genuine remorse by the grace of Jesus’ cleansing blood, and AFTER they have repented (CHANGED), NOT BEFORE. That is the formula for forgiveness which God models for us, and that is the formula which he instructs us to follow. ”

HeadHeartHand.org: “4. God’s forgiveness is conditional upon repentance (Luke 13:3; 17:3; Acts 2:38): God’s forgiveness is conditional upon the offender wanting forgiveness and wanting to turn from His offending ways. 5. Forgiveness through repentance produce reconciliation on both sides: Offering forgiveness reduces the temperature of the conflict; but only the giving of forgiveness, in response to repentance, ends it. ….We must be willing, ready, and eager to forgive everyone….We must offer forgiveness to everyone….Some people say, ‘I can never forgive until Jim repents.’ If so, you are going to carry around a huge and growing load of resentment as you pile up unresolved conflicts in your life.”

ThoughtsTheological.com: “Nevertheless, when we take the initiative in extending forgiveness, prior to repentance on the part of the criminal (as Christ died for us, while we were still sinners), we are expressing our willingness to give up our personal grievance against that individual, a readiness to bear the cost of this gracious act ourselves. But, as in the case of God’s relationship with sinners, reconciliation between us and the one who wronged us can only be brought about by the transgressor’s repentance. Our offer of forgiveness is not dependent upon his repentance, but the reconciliation between us, which brings to fruition our act of forgiving, is conditional upon his acceptance of his forgiveness which necessarily entails an admission of his guilt and a genuine sorrow at the (possibly irreparable) harm he has done.”